Dharma Tradition is Indic[1] Nationalism

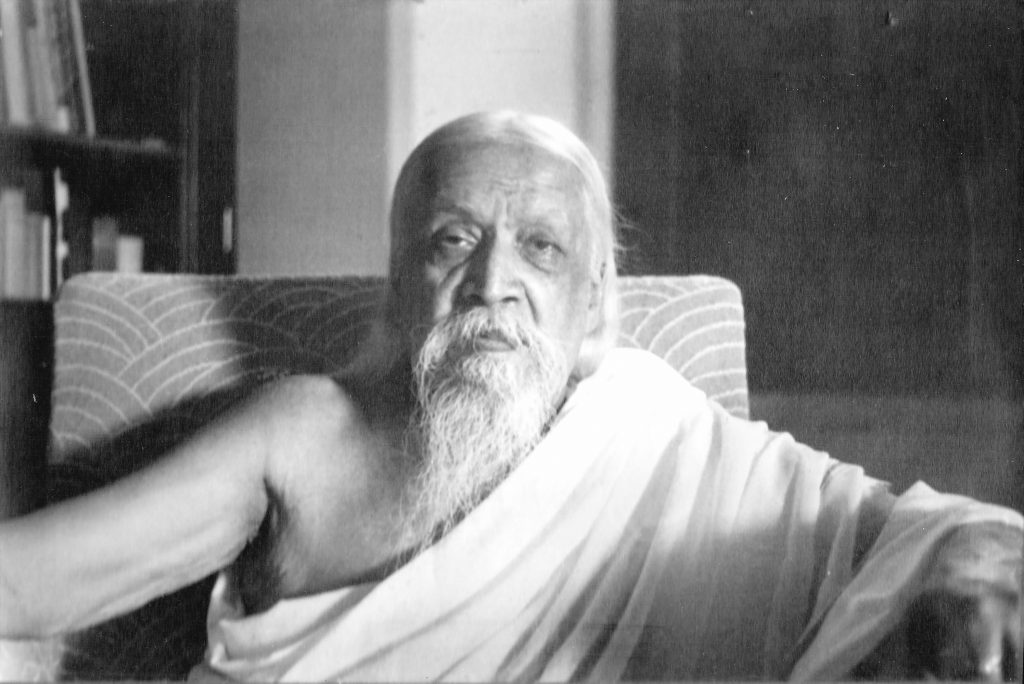

Dharma tradition, one of the oldest social systems, has its own socio-political narrative. This narrative can, arguably, be identified with Indian nationalism which, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, was founded upon principles of Dharma. For instance, Sri Aurobindo[i]—in his Uttarpara speech in 1909—explained this connection:

When you go forth, speak to your nation always this word, that it is for the Sanatan Dharma that they arise, it is for the world and not for themselves that they arise. I am giving them freedom for the service of the world. When therefore it is said that India shall rise, it is the Sanatan Dharma that shall be great… When it is said that India shall expand and extend herself, it is the Sanatan Dharma that shall expand and extend itself over the world. It is for the Dharma and by the Dharma that India exists. I say that it is the Sanatan Dharma which for us is nationalism. This Hindu nation was born with the Sanatan Dharma, with it it moves and with it it grows. When the Sanatan Dharma declines, then the nation declines, and if the Sanatan Dharma were capable of perishing, with it the nation would perish. The Sanatan Dharma, that is nationalism.

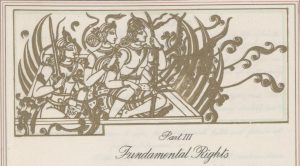

Being inspired by this narrative, the Indian leaders in the early decades of twentieth century refused to acknowledge the western worldview and insisted on “swaraj” as the political goal rather than mere independence from British rule. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a famous nationalist of those times, who is often quoted as “Swaraj is my birth-right and I shall have it”, wrote a commentary on Gita, The Gita Rahasya, that explained dharma as the key to his socio-political narrative.

Being inspired by this narrative, the Indian leaders in the early decades of twentieth century refused to acknowledge the western worldview and insisted on “swaraj” as the political goal rather than mere independence from British rule. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a famous nationalist of those times, who is often quoted as “Swaraj is my birth-right and I shall have it”, wrote a commentary on Gita, The Gita Rahasya, that explained dharma as the key to his socio-political narrative.

“Swaraj” literally means Rule of the True Self. Dharma traditions acknowledge everyone’s True Self as self-same Pure Consciousness, often called the Atman.[ii] Generally, nationalism means devotion to one’s own motherland, acceptance of almost everything that belongs to the motherland, and at a minimum, mild rejection of everything that is foreign. However, Indic Nationalism is much deeper than this mere geographical notion of nationalism. Ram Swarup, a profound thinker of the twentieth century, expressed the essence of Indic Nationalism, which was narrated[iii] by Sita Ram Goel in his book How I Became Hindu: Swarup said, “But foreign should not be defined in geographical terms. Then it would have no meaning except territorial or tribal patriotism. To me that alone is foreign which is foreign to truth, foreign to Atman.”

The critics of nationalism often point out that being born in a land is not a matter of choice for a person. Therefore, being proud of one’s motherland is nothing extraordinary. Indic Nationalism is love for the motherland on account of a society that upholds the socio-political narrative of the Dharma Tradition in a continuous manner. And, there is every reason to be proud of being born in a society that has a continuity for thousands of years and has exclusively upheld the rule of the True Self. This ancientness and continuity of Indic civilisation makes it imperative for the members in the society to offer their duty to their society so that the reign of the True Self remains established in their society. This duty-mindedness is the ultimate essence and meaning of Indic Nationalism.

Historically, Indic Nationalism rarely called for territorial conquest but rather focussed on founding Dharma-based societies in other lands, as opposed to European origin nationalism. Even Han nationalism that emerged as the Chinese nation, has forever aspired for territorial conquest and annexing new lands. On the contrary, Indian kings always strived for inculcation of Dharma tradition among people of different lands without aspiring for military conquest and needless bloodshed.

In all probability, our Constitution-makers were not blind to this aspect of Dharma which is why they did not include the word “secular” in our nation’s constitution. This omission is likely on account of their understanding of the historic role of Dharma in facilitating governance and administration in India, which would be excluded on specification of the word “secular”. For instance, B. R. Ambedkar regarded Dharma as rational and relatively free of colonial bias. He was also supportive of a fundamental differentiation between Dharma and religion:

I regard the Buddha’s Dhamma to be the best. No religion can be compared to it. If a modern man who knows science must have a religion, the only religion he can have is the Religion of the Buddha. This conviction has grown in me after thirty-five years of close study of all religions. (Preface to The Buddha and His Dhamma)

The above statement clearly shows that Ambedkar was aware of scientific nature of Dhamma—the term for Dharma in Buddhist tradition—and made an analysis of different claims of truth without limiting himself to a faith based imposition.

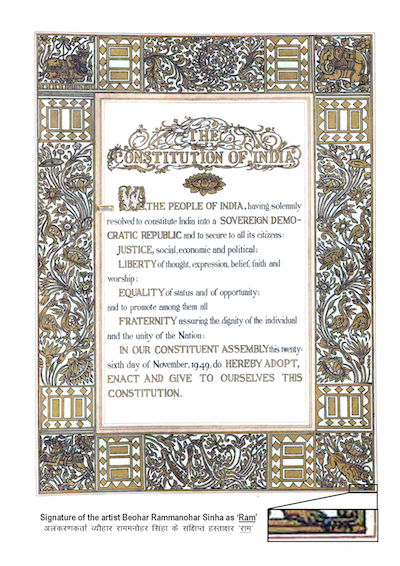

Not only Ambedkar, but the motifs drawn on the original copy of the Indian Constitution by Nandlal Bose and Beohar Rammanohar Sinha, have also been heavily inspired by the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and Sri Buddha apart from diverse historical figures.[iv] These motifs demonstrate that the Republic of India formed on November 26, 1949 was viewed as a civilizational continuity of our Dharma tradition rather than a new nation being forged.

Dharma and Secularism

Things, however, took a sharply radical turn in the post-independence era. The Indian elite have swallowed socio-political understanding of the western lands. Dharma is a word in Indic languages, which is non-translatable in English. Language is often said to be a matter of convention. Therefore, a particular culture may actually understand a word very differently than another one. For example, the word “secular” bears very different connotation to an Indian as opposed to a European. In Europe, a secular person will proactively fight for the right to criticise religious dogmas. Karl Marx said[v], “The criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism.” Interestingly, an Indian secular icon may very well consider criticism of a particular religion inherently as an anti-secular exercise.

Koenraad Elst provided a fine example in his book Decolonising the Hindu Mind (2001) in the backdrop of Indian Government’s banning of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. He cited Professor S. Guhan, a noted academician and secularist, who argued that banning any book that criticises Islam, is in the interest of secularism. This position, summarily speaking, describes the worldview of many of the Indian secularists, if not most.

When the same word, secular, can mean two diametrically opposite ideas under two cultural hegemonies, we understand the gravity of the problem of translation since the word

Dharma, has no synonym in English at all[vi]. This powerlessness of the highly-enriched English dictionary is a living testimony to West’s lack of exposure to an indigenous Dharma tradition for centuries. Since the West is almost ignorant about the Dharma traditions, naturally they have no understanding regarding socio-political institutions under the Dharma traditions.

To make matters worse, the Indian elite have followed the West in their education, in their socio-political institutions and in their narrative, thereby growing up without any knowledge about our Dharma traditions. When these elites formed their narrative about India, that narrative was devoid of any role for Dharma. The elite in India started learning about dharma in English which translated the word as “Religion”. In their colonised understanding, dharma became the primitive religion of India.

As the cultural roots of the elite have been cut off, they have become a susceptible target for a doctrine that least emphasises the importance of culture on human aspiration and human destiny. Marxism is exactly that very doctrine.[vii] Marxist sociology considers production as the base, and religion and culture as the superstructure—the base influences the superstructure but not vice versa. In other words, man’s emphasis should only be on factors of production, usually never on culture.

Dharma was, therefore, relegated to a very tertiary factor of the human civilisation, in that worldview. Moreover, Marxism, in particular its dialectics on Class Struggle, presents a linear history. Therefore, the contemporary technological inferiority of India was translated as perpetual technological backwardness of India. And, since factors of production essentially shape culture and religion under the Marxist paradigm, technological backwardness of India is translated into cultural inferiority of India. Dharma has become, to the colonised elite, India’s primitive religion whose demise per se would ensure India’s rejuvenation!

This linearity is utterly flawed as historically India was one of the most technologically advanced countries, till the first millennium AD, when the Dharma Tradition was strong in India. The reader may observe the European scientists’ recognition of Indian technological superiority by referring to Dharampal’s Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century. History of Indian Science and Technology (HIST) project by Rajiv Malhotra’s Infinity Foundation documented ancient Indian science and technology through many volumes.[viii]

Even though, a part of the elite—who are particularly not driven by any leftist ideological zeal against religion—acknowledge people’s right to practise dharma without being mocked, they consider it at best an exercise of personal freedom without any scope for socio-political narrative-making by dharma tradition. Consequently, Dharma tradition was left neglected dying a slow death.

Historically however, Indic education system, was centred around dharma: every Indian child used to start his writing in a temple a hundred years ago. But the Indian elite pursued separation of education and dharma as an ‘agenda’. Within a span of two to three generations, Indians forgot their own social and political institutions that have been sustained by dharma.

Decolonisation and Dharma Tradition

Decolonisation of India is yet to happen[ix]; but slowly and surely the colonised elite are being challenged in the realm of intellectual discourse. Post economic liberalisation, India has a sizeable English-educated middle class who are professionally successful. They are neither afraid of intellectual discourses in English (as was the case for many one or two generations ago) nor suffer from lack of information thanks to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) revolution. Some of these people are challenging the hegemony. Unless economic liberalisation is reversed, their voices can, no way, go down. Although most of the energy is being spent to call out only the ideological bankruptcy of the existing elite, eventually the focus will be on discovering Indic nationalism that is the Dharma tradition. Therefore, at this rate, the dharma tradition and its worldview will naturally be relevant again to Indian polity.

[1] The difference between Indian and Indic: The word Indian specifies something that belongs to the geographical boundary of India; Indic represents something that originated in India.

Ideas generally have no geographical boundary; hence many ideas that originate elsewhere in the world can find resonance among the Indians. For example, Nationalism is essentially a western concept but it appealed to a section of the Indian elite in the nineteenth century and twentieth century, which is why it is called Indian Nationalism.

Indic Nationalism means the notion of nationalism that originated in India and somewhat in variance with the western notion of nationalism.

[i] Aurobindo, Sri. Sanatan Dharma: Uttarpara Speech. Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram (1983). Also available at http://cw.routledge.com/textbooks/9780415485432/24.asp.

[ii] Buddhist traditions often consider everything as Anatma that is nullity as one’s True Self. Such a notion does not jeopardise the idea that everyone’s True Self is one and the same.

[iii] http://www.voiceofdharma.org/books/hibh/ch7.htm

[iv] http://www.opindia.com/2016/01/the-hidden-beauty-within-the-indian-constitution/

[v] A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Karl Marx available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/critique-hpr/intro.htm

[vi] Ram Swarup discussed the specific meaning of Indic words that goes beyond intellectual domain in his monumental work, The Word as Revelation . The problem of non-translatable Indic words is also elaborated well by Rajiv Malhotra in the fifth chapter of Being Different.

[vii] For a clear exposition of the Marxist arguments, one may consult A journey from the Volga to the Ganges, a fantastic story-telling by Rahul Sankrityayan.

[viii] http://rajivmalhotra.com/books/buy-infinity-books-india/.

[ix] Koenraad Elst’s Decolonising Hindu Mind discusses Indian elite’s cultural colonisation.