The post A Sanatani Atheist: In Search of My Freedom of Expression appeared first on Dharma Today.

]]>You were born in a Muslim family. Did you grow up in a Muslim society? How did you develop early doubts about religion and God?

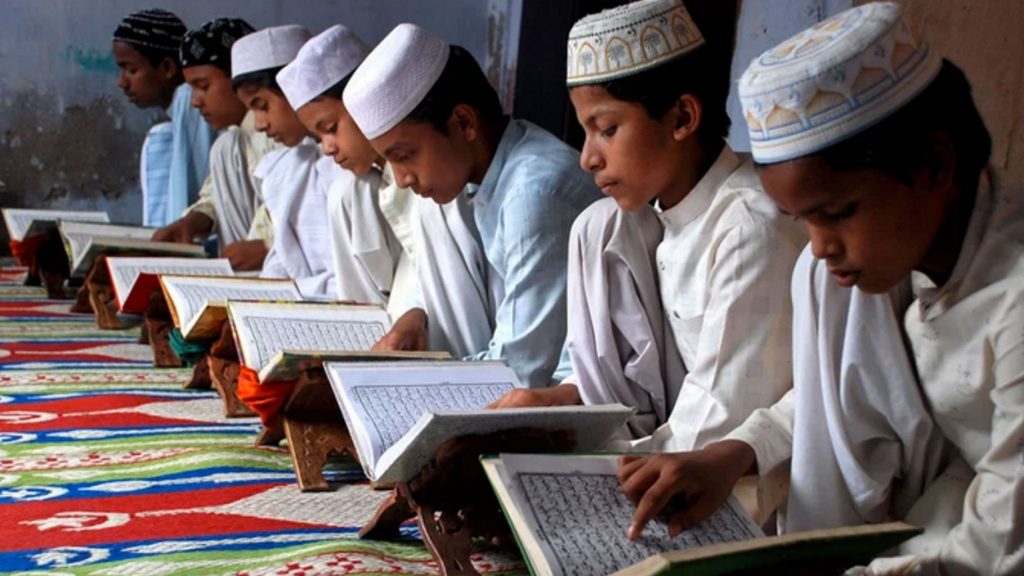

I spent the first 21 years of my life in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. In my childhood, my recital of Quranic Surahs earned me praises from the teachers at the Madrassa where I was taught. When I grew up a bit and still in school, I was confused to reconcile the Quran with the world of reason. It was said that Allah causes rain through his angel Mikail depending on human needs. If so, I questioned, why don’t we ever see any rainfall in the Sahara desert? The scientific theory of the water cycle looks much more promising rather than the Quranic theory, isn’t it?

What was the reaction of your teachers?

The Maulanas could not answer these questions of mine but got furious and condemned me as Kaffir. I wasn’t discouraged by it. It pushed me towards studying more deeply on these topics.

How did your parents and the society at large react to your scepticism?

I asked my mother flatly if she considered the Quranic description of her being a place of husband’s sowing of seed (the Quran 2:223) disrespectful. She was unhappy with me for questioning Allah.

Should God not reward good deeds like work of Mother Teresa for the downtrodden, instead of observing who is praying to Him and who is not? Why should He be bothered about such petty-minded notions? I did not restrict myself from these discussions at my workplace at Medina and was fast becoming persona non grata. I was not a complete disbeliever back then but merely a sceptic. When words were out in the air that I would be fired from my job, I even used to pray to Allah, “O Allah! Let me not get fired from my job. I am only asking for my just right of earning by my hard work.” How innocent was I back then!

Were you then fired? What happened to your skepticism after then?

I was fired within a few days. The rumours were correct. After being fired, the skeptic in me became firmly an unbeliever!

You are one of the famous atheist bloggers of Bangladesh ,consistently and systematically being targeted by the Muslim Fundamentalists. How did it start? What made you an activist of Atheism?

From Riyadh, I came back to Dhaka, Bangladesh and got married to my cousin. I was in my early twenties that time. By then, I completed my Bachelor’s degree in computer science. I also have my proficiency in graphics designing and making cartoons. On account of my skills, I found a coveted employment in Central Depository of Bangladesh Limited. I fathered a son a year after my marriage. I became a full-fledged family man. The life was, then, rather smooth for me.

I started posting couplets on different themes in social media and was becoming popular. One of my couplets was that Creator and a creative mind, both, love listening to own praises. Controversy erupted when Muslims challenged me on the Creator part of this couplet. I pointed out to the text of the namaz, that is the first Surah of Al-Fatiah from the Quran and it is no different than an explicit flattery of Allah. I also highlighted that it was made mandatory by Allah Himself for Muslims to recite this namaz five times daily.

My writing eventually appeared as a book entitled Nāstika which made me famous; though now I see that book rather amateurish. I also made an exhibition on graphical art on the theme Cogito ergo sum (I think; therefore I exist). In the newspaper called the Daily Star, the exhibition received critical acclamation. This was also not liked by the Muslim fundamentalists.

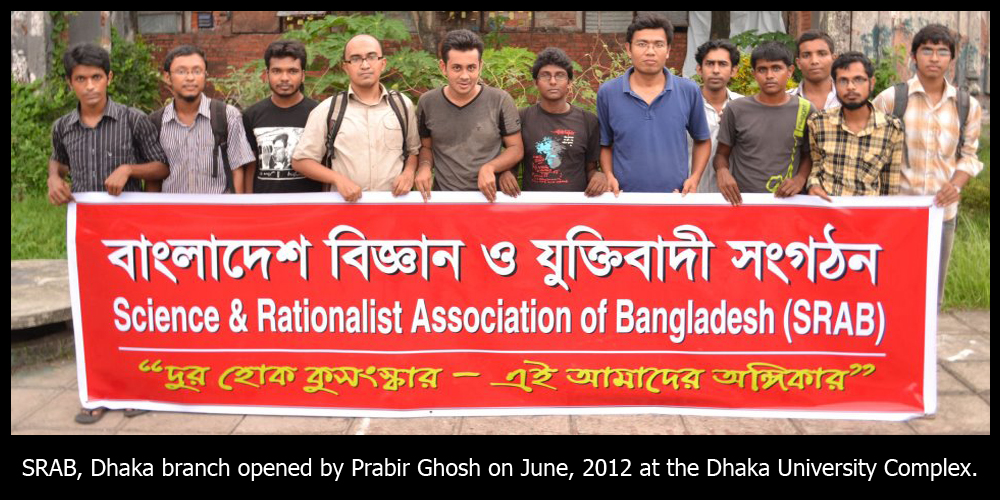

It was no less than a dare to publish this book Nāstika and also some other books under my real name and with my photo in Bangladesh. I was welcomed into the budding rationalist atheist movement of Bangladesh and got connected to intellectual luminaries like Asif Mohiuddin, Ahmed Rajib Haider, Avijit Roy and Prabir Ghosh. I was an organizer for the organization Science and Rationalist Association of Bangladesh, in short Sraban. We used to make fun of astrologers and miracle healers. I developed deep friendship with persons like Niloy Neel and Tasib Hassan. Tassib is absconding right now from the Muslim fundamentalists. Niloy already left all of us….

What was the agenda for your activism? What was the main message you were highlighting to the people of Bangladesh?

The people of Bangladesh took a stand to assert their Bengali identity in 1971 during their War of Liberation against Pakistan and opposed the imperial imposition of Urdu. The Pakistani authorities were openly communal. Yahya khan, the then president of Pakistan, instructed his soldiers to rape the Bengali Hindu women to impregnate them all with Muslim children only. The inglorious organisation Jamaat–e–Islami Bangladesh and its leaders like Ghulam Azam and Salahuddin Quader Chowdhury were in cahoot with the Pakistani oppressors.

Yet, after the assassination of Sheikh Mujibar Rahman in 1975, the historical course took an unwarranted new turn. Ziaur Rahman as premier, offered succor to Jamaat–e–Islami Bangladesh, once again. The history was distorted in suppressing the role of Islamist Rājākārs and their anti-national acts during the Liberation War. Education was gradually taken over by the Muslim fundamentalists with increasing Arabisation of Bengali language and expulsion of Hindu authors from the school textbook. The sapling Ziaur planted, has grown into the poison tree over the last four decades. Now, Bangladeshis largely sympathise with Pakistan, their once oppressor, and mostly hate India, their liberator. It became a Muslim country falling from its secular ideals. I was becoming aware about the true history of my nation this time and also became aware of pervasive distortions regarding historical facts.

We were also participating in philanthropic activities and protesting the targeted heart-rending atrocities against the minorities (the Hindus) of Bangladesh. As a typical case, take a Hindu family consisting of a widowed mother and an adolescent daughter of 13 years old. Seven hooligans came at night—two were raping the mother and the other five together gang-raping the daughter. The mother, while being raped, was begging to those rapists to not rape her daughter all together but one by one as she is too young for such an assault. We highlighted these beastly atrocities which generally receive support from the Muslim fundamentalists.

How did such so-called religious people justify their barbarism?

The agenda of the Muslim fundamentalists is to define any opponent as Kaafir and then remove all such kaffirs from Bangladesh. Encouraging hooligans to persecute the Hindus is a strategy for them to create a kaffir-less Bangladesh. And, their strategy is winning as well. The falling population share of Hindus and Buddhists of Bangladesh over time, from close to 30% of the population to less than 10% today, is a fact.

You were associated with the now-legendary Shahbag movement. Was it this time when this movement was born? How was the movement born?

On the fifth day of February, 2013, we, more precisely only 26 of us, started a non-violent movement to highlight the issues with Rājākārs. I wrote and published a book that time exposing the Rājākārs, entitled Rājākārer Keertikalāp (“Glorious” Deeds of the Rajakars). We were using our artistic talents to attract public attention. In the first day, we were ridiculed and laughed at. But soon, we received considerable public attention. The Ekushey Book Fair on the occasion of Bangladesh’s Independence Day was taking place and when people were coming to that book fair, we highlighted to them about the persecution we Bengalis faced by the Rājākārs who not only evaded the law but also rose to prominent posts.

We collected signatures of scores of thousands of passers-by who were convinced of our cause of demanding capital punishment for these Rājākārs accused of heinous crimes. We submitted their signatures to the authorities. This movement was widely highlighted in the international media. At that juncture on 15 February 2013, one of us, Ahmed Rajib Haider who used to express his atheistic worldview under the pseudonym Thaba Baba, was hacked to death by the Islamists. Sword was used to silence the pen. Starting from the next day, attendance at our protest dropped significantly. We held the funereal of Rajib at Shahbag itself but the movement was losing stream after having suffered from political intrusion.

What happened then on the March 7, 2013 when you were severely wounded in an assassination attempt?

Within three weeks of Rajib’s death, I was coming back to my home after attending a programme in a public bus, two persons aged about 20 in Islamic attire started following me. Another person in similar attire came in front of me and on his gesture, these two persons from the back assaulted me with machetes. I suffered deep injuries in my head, shoulder and chest. I did not panic and ran in my bloodied state to take cover and reached a traffic police box. I am pretty sure, that run would have earned me a Gold Medal at the Olympics. (laughs)

The police promptly took me to the nearest hospital and after receiving first aid there, I was transferred to the Dhaka Medical College. I was admitted there for weeks and was healed with time although my left side was partially paralysed for many months.

Did you receive support from the society against these deadly attacks on you?

Not really. On the other hand, my attackers enjoyed support from the very top echelon of the society to all the way down. When I later registered the case of the assassination attempt on me with the police, the policeman present there was unhappy to know about my atheistic inclinations and wryly commented that I was the one who should first be arrested. Can you just imagine that!

Pressures were building upon my family—my wife and in-laws—to withdraw the case against the Islamist attackers, from all quarters including the police. My employer categorically told me that my atheistic assertion made my colleagues avoid my company. And, I was forced to resign from my job.

This continuous pressure from all quarters made my wife divorce me to avoid living a dangerous stressful life.

I became an ultimate social pariah. I was given nominal police protection but I was convinced that the threat to my life would persist as long as I remained in Bangladesh. Sympathetic police officers too told me privately that if a change in political power took place with a person with stronger connection to Muslim fundamentalists, then I might even be arrested.

We see. It was impossible for you then to go back to live your normal life after this murder attempt. How did you survive then?

I emigrated to Bahrain, a relatively secular country, in the Middle-east in November 2013 and took a job employing my skills in multimedia and creative work. I simply disappeared from the rest of the world and lived a dormant life.

But you could not remain long dormant, could you?

I was shaken altogether again on 7 August 2015 when Neeloy Nil, my good friend, was hacked to death in Bangladesh because of his atheistic beliefs. I decided again to voice myself using social media against the intolerance of Islam. My activism earned me many admirers in the social media. This time I was cautious and did not reveal my real location to anyone.

I used to be the only executive in my office when I used to post things in the social media. All others in my office were manual workers, although from Bangladesh. I did not see this coming that some of them reported to my employer regarding my atheistic outlook and activities. A conspiracy was hatched against me. One day they had tactfully secured their official secrets from me. When I reached home that evening, I was fired over a telephone call. Gradually I came to know that a case of blasphemy has been registered against my name that would translate into a prison sentence of 15 years for me. I found myself alone cornered in a foreign land with even my passport in possession of my erstwhile employer who had turned hostile.

So your employer took exception of your atheism, really harshly. Did you get a chance to explain your case to him?

I had to surrender to my employer even after he had fired me most unethically and also deprived me from my due benefits as an employee. He categorically told me to leave Bahrain same day. My repeated pleadings to him fell into deaf ears. He was adamant and he did not even care about the precarious state of my life in Bangladesh if I had been made to land in there. Immediately I was boarded by him on a flight to Dhaka.

Again at Bangladesh! You escaped to Bahrain from Bangladesh to secure your living and freedom of expression. How did you respond in such a difficult time of your life?

I managed to call my mother over phone from the airport and told her to purchase a ticket to Kathmandu, Nepal for me. I landed in Dhaka airport and did not even set foot outside the airport. She came over as visitor inside the airport and handed me the ticket. Next day from Kathmandu, I took an enormous journey to India for about 18 hours. I crossed the border to India taking help from one of my contacts—it was a quite simple affair at the end.

Why did you choose India?

Through social media, I have a long list of friends in India. I was helped by some of them to get a temporary legal stay in India.

What is the difference in cultural attitude between Bangladesh and India from an atheist’s viewpoint?

In Bangladesh, my life is at stake for my atheism, but lakhs of people, actually persons in influential positions, are atheists in West Bengal. They can express their opinion freely and fairly. People from both West Bengal and Bangladesh are Bengalis and from the very same culture. The only reason that I cannot express myself freely in Bangladesh is that it is a Muslim majority country while West Bengal is still not one. And, I know for sure that the day West Bengal becomes Muslim majority, I would lose my freedom of speech.

In fact, many Bengali intellectuals in West Bengal look for a Hindu-Muslim unity across the border, between West Bengal and Bangladesh. Your take?

Often people quote the line written by great poet Kazi Nazrul Islam:

We are two budding flowers together, the Hindu man and the Muslim man.

I retort back:

Oh Dear! Oh Dear! Then why did you break India and create Pakistan?

Riyadh to Dhaka to Bahrain to India—your long journey was more of a mental development. Of developing better and better understanding about the world around you. What is your identity now?

Biologically I was a human being when I was born like I am now. I, today, say with pride that culturally I am a sanatani—the follower of the eternal tradition, the Sanatan Dharma. Had some Muhammad Ghori or some Ikhtiyar al-Din Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji not converted my ancestor on the point of sword to Islam, I would have grown up chanting a hymn in my own language rather than uttering prayer in a foreign language.

What is your attitude towards Hinduism?

Because of my background, my knowledge of Hinduism is limited. I am always against the oppressor and with the persecuted. I found my voice in the following verse of the Gita (4: 7-8):

Yada yada hi dharmasya glanirbhavati bharata

Abhythanamadharmasya tadatmanam srijamyaham;

Paritranaya sadhunang vinashay cha dushkritam.

Dharmasangsthapanarthaya sambhabami yuge yuge.

This verse clearly says that the oppressor will be defeated and the persecuted will receive the final justice. Can any word of the world be sweeter than this couplet?

Do I believe in everything of Hinduism? Hell No! But I know something for sure: Hinduism can be changed, it can be reformed. Two hundred years ago, Sati (immolation of wife in husband’s pyre) was part of the Hindu tradition; today not a single Hindu even considers its reintroduction.

You are a victim of Islamism and like in Bangladesh, Islamism has become a recurrent problem in many Muslim societies across the world. However, most Muslims are good persons irrespective of the theology of Islam. Atheists like Sam Harris feel that the attack should be against the Islamic Theology which is at the source of the Islamism problem. On the other hand, people like Maajid Nawaz or Ayaan Hirsi Ali feel that taking a direct hit at Islam will mean a terrible bloodshed as innocent Muslims will be in a dilemma. The best thing to tackle Islamism is to reform Islam.

What do you think about it? What is the most humane solution to this problem?

Yes, it is definitely true that most people in a Muslim society are peaceful. If there are a hundred violent muslims, more than a lakh of the peaceful moderate muslims remain in the same society. The only problem is that these moderate muslims act as apologists for the violent muslims. What we require is to bring out the truth about Islam to all Muslims. Let them study Quran and understand if we need this Quranic Law for the civilised human society of today. Why the attack happened against me? A clear possibility is that I could match the Islamists to discuss the Quran with my knowledge of Arabic, which they could not digest.

At the same time, Madrassas must be closed and modern education should be imparted to all the Muslims without exception. Vigilance must ensure that funds and operational facilities remain outside the reach of the Jihadi Muslims.

Do you have any final word to offer to the readers of this article?

My final submission to the Hindus and to the atheists: If you do not read the Quran being a Hindu or being an atheist today then you will have to read it tomorrow being a Muslim.

The post A Sanatani Atheist: In Search of My Freedom of Expression appeared first on Dharma Today.

]]>The post Are Dharma and Religion the Same? appeared first on Dharma Today.

]]>Mistranslation of Dharma as Religion

Often dharma is translated as religion in the absence of a proper synonym in English. This has been challenged by many scholars. Prof. S.N. Balagangadhara, an insider to the western academia, pointed out this “non-religious” construct of the Dharma tradition. In his book “The Heathen in His Blindness”: Asia, the West and the Dynamic of Religion (1994) he presented his thesis that demarcates the Indic tradition from the Abrahamic tradition. This scholarly and rigorous book is well-acclaimed. Balagangadhara is, currently the director of the India Platform and the Research Centre Vergelijkende Cutuurwetenschap (Comparative Science of Cultures) at the Ghent University, Belgium.

In the preface of this book, Balagangadhara clarifies that appreciation of his thesis demands from the reader—either the Western one or the colonised elite of a non-western nation—a dissociation from her/his cultural background who, knowingly or unknowingly, grew up under the influence of a Christianity induced culture. Therefore, his book presents the arguments keeping the cultural background of the potential readers in mind.

The book, rather unconventionally, addresses the reader in the second person to emphasise the non-universal nature of any culture-based dialogue and non-translatability of culture-based words. It is perfectly possible to translate a sentence like “It rains” or “It is sunny” in all languages of the world of all times, since all cultures have witnessed the rain and the sun in their experience. In the cultural sphere, experiences of different groups are quite different, and therefore, one set of cultural constructs may not be translated into another language. What is more significant is that this mistranslation of initial set of cultural constructs may prepare ground for further and more serious misunderstandings.

Let us do a thought experience to illustrate this idea through an example in the physical sphere. If any of us lands up in a stone-age world, we will not have any difficulty to translate the physical phenomena like the sun or the rain of that world. However, if we teleport a stone age person to any of our modern cities, he will be short of his vocabulary while viewing the modern technological marvels like electricity that allows the modern citizens to switch on a light by pressing a button far away. The wonderstruck stone-age-person may call electricity as ‘magic’ for want of experience. He may incorrectly presume all citizens as magicians and may attribute imaginary attributes to these “magicians”.

Although only a thought experiment, it presents an analogy to the prevailing cultural situation. A spiritually advanced diverse culture like India (the modern day citizen) can readily understand the monolithic constructs of another society (the stone-age person) but the gaze reversal causes umpteen misconceptions. Therefore, the Western academy presents Buddha as a rebel to Hinduism (the alternative terminology used is Brahmanism) and considers him to be the founder of a new religion that is antithetical to Brahmanism. This western understanding seems quite ridiculous to the Dharma tradition for the following reason.

![]()

The Western academy conceives Buddha antithetical to Brahmanism like Marx is anti-Capitalism. Could Marx ponder over the question as to who is a “true” capitalist and attribute all noble Marxian qualities to a “true” capitalist? The answer, would be, an unequivocal No! Buddha, the so-called “anti-brahmin”, inexplicably for a western scholar, did define a “true” brahmin in several places (For example Dhammapada 417, 81 quoted in The Heathen in His Blindness page 208) and the “true” Brahman defined by Buddha is the most honourable person, says Buddha. This is a paradox that is beyond the western scholars to resolve.

A dharma-practitioner sees no contradiction in this phenomenon. To him, Buddha presented his realised idea that meditation is more conducive to peace than yajna with animal sacrifice. There are others like Vasu, the King of Chedi, who also opined the redundancy of animal sacrifice; he is also respected in the rituals of so-called Brahmanism.[i] A true brahmin—that is, a knowledge seeker, as commonly understood in the Dharma tradition—definitely knows the means to peace and would be most honourable to Buddha.

The conclusion of Balagangadhara is plain and simple: Indian society is marked by absence of religion.

What is Religion?

Religion is defined, in the Oxford dictionary, as the belief in and worship of a superhuman controlling power. It is a cosmology, some kind of theory about human destiny.

Religions require Faith unlike dharma which is scientific exploration of human psyche. To a scientific practitioner of Dharma, this difference is crystal clear. This difference—however—cannot be even recognised by those who do not undertake dharma-practises. Those who practise dharma rituals without the scientific attitude, may also find both dharma and religion as a matter of faith. Giants in the tradition of dharma, suggested rules for socio-political discourse and development of personal consciousness, based on their own experience which is potentially verifiable by all. In religious traditions too, the Prophets shared their commandments to their followers who must follow them for rich after-life benefits. Differentiation between these two sets of rules may be confusing for many.

What Differentiates Dharma from a Religion

If religion is simply a faith, many sects of the dharma tradition may be called faiths too. Any doctrine under the dharma tradition, however, must adhere to satya and ahimsa, which is not a requirement for a religion. In the Indic tradition, doctrines are of two kinds: dharma and adharma[ii] where the latter do not subscribe to satya and ahimsa.

An Analogy on Dharma and Religion

Analogies are seldom perfect, yet I tread the risky path for a better understanding. A Dharma-theory may tell us, if we do not add water to the car-radiator, the car-engine may suffer on account of overheating. A Religion-theory, on the contrary, will be: if we do not keep the photo of Vishvakarman—the devata of engineering—beneath the windscreen, we will end up hurting the car-engine. To an unintelligent person, a false equivalence may arise between the two theories, as both suggest about following a rule and imply disastrous consequences of not following the rule.

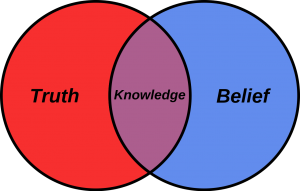

Truth and Ahimsa: The Touchstone

Now, which of these two theoreticians will be more secured? Which of them will be more prone to violence? If I do not want to add water to my car-radiator, Dharma-theoretician would perhaps smile at me and retort to me, “Yes go ahead; examine my words”. He will not be perturbed by my lack of faith and is least likely to throw any violence. On being told about my reluctance to hold the photo of Vishvakarman, the Religion-theoretician would, unlike Dharma-theoretician, be prone to—directly or indirectly—blaming me for my lack of faith in Vishvakarman, which is initiation of violence in the subtlest form.

In essence, ahimsa is an action-policy emanating out of satya. Therefore, satya can be verified from the practise of ahimsa, and ahimsa is reinforced from a true understanding of the universe, satya. They are complementary and supplementary to each other. Without pursuit of satya, one cannot practise ahimsa for long. For a satya-less doctrine, the inquisitive minds are to be silenced using some kind of himsa. On the other hand, without practice of ahimsa, the pursuit of satya is impossible. The course correction to reality will be blocked by easy choice to mute the critics through himsa. Consequently, satya may be subjugated to human greed and personal ambition.

Divergent Action-Policy by Dharma and Religion

While in verbose theory-making, one can term one’s own religion with grandiose adjectives like religion of peace, religion of love etc., the real examination of its type—dharma or adharma—can be done by analysing the action-policy. If the action-policies of any religion do not adequately emphasise satya and ahimsa, it is not dharma.

Satya is reality. Analysis of reality requires complete freedom of expression and thought to all. A dharma-based policy will neither take away one’s personal freedom to thought and expression nor will stifle criticism in any form. A dharma tradition will never be interested in book-burning or book-banning but in comparative analysis of various truth claims. On the other hand, a faith based religion is never interested in real debates but stifles others’ right to criticism whenever possible.

In ancient India, Charvaka who was grossly opposed to the fundamentals of the Dharma tradition, was allowed to express his thoughts. Buddha who pointed out insignificance of many rituals practised by Indians of those times, preached his idea to dharma-practitioners without any threat. Such respect for satya is not observed in the present day secular India where criticism of a religion is virtually banned under the Indian Penal Code article 295.[iii]

Furthermore, dharma can never suggest any physical, mental, cultural, emotional aggression against “the Others”, in its pursuit of ahimsa. Anybody, in the light of this divergent course of action policy, can judge what is dharma and what is an adharma-based religion. Any sect in the dharma tradition must emphasise a single policy for the entire humanity whereas many a religion divides the humanity among believers and the non-believers. Here such a religion commits the primal act of violence.[iv]

Dharma’s View of Religion

Religions may or may not have originated from a Dharma-tradition; they may or may not have scientific roots. In case a religion can trace its origin to a dharma tradition and its rules resonate laws derived in first-person-empiricism based science, we can think about this religion as one that inherits some aspects of dharma. For those who are comfortable with the parlance of Marxian sociology, the science of dharma is the base, on which the superstructure of this particular religion is founded.

For example, Hinduism—a so-called religion of the present times—is founded upon the science of dharma. One should not, nevertheless, prone to a conclusion that every aspect of Hinduism reflects the science of dharma. The science of dharma, as argued in this article, is the highest expression of human consciousness and time to time, adherents of the dharma-tradition deviated from that stage of the highest consciousness. Such deviations produced outgrowths that are, no way, expressions of the science of dharma.

In the words of David Frawley, there are more religions inside of Hinduism than outside of it. This is indicative of two things. One, satya and ahimsa allows sustained harmony among sects inspite of diverse outlooks. Second, without explicit focus on satya and ahimsa, harmonious existence and cultivation of diversity is impossible.

“Sarva Dharma Sama Bhava”

This is a well-articulated phrase in contemporary Hinduism which often passes off as its essence.[v] This phrase is a tautology if it is taken in its true meaning. “All dharmas are of the same inclination”. Indeed all different doctrines or facets of dharma, by definition, must cater to the twin theme of satya and ahimsa.

Yet, the popular meaning of this phrase is “equivalence (equality) of all religions” which is quite nonsensical. The Abrahamic religions whose cosmology describes one finite human life and an infinite afterlife of Hell or Heaven depending on faith in a particular Prophet, is no way equivalent, similar or even comparable to the Dharma tradition cosmology that describes reincarnation till absoluteness is achieved.[vi] They are simply different, as Rajiv Malhotra has convincingly demonstrated in his book Being Different (2011). The fact that the nonsensical meaning of this phrase has become a main plank of Hinduism, indicates the downfall of Hinduism from a dharma-tradition to a faith (religion).

[i] The brahmins and the devatas both disputed on the need for animal sacrifice in yajna. The former group insisted on animal sacrifice but the latter group pointed out its redundancy. They came to Vasu, the King of Chedi, for arbitration. Vasu offered his verdict in favour of the latter group. This resulted in vegetable sacrifice in yajna instead of animal sacrifice. The brahmins got angry and cursed Vasu to being famished. The devatas came to his rescue and mandated the ritual of Vasudhara, wherein people offer rice and ghee to Vasu.

[ii] The sixteenth chapter of the Gita makes a categorisation of Daivi and Asuric natures. This categorisation is very similar to the dharma-adharma categorisation.

[iii] This law is not isolation but continuation of the secular policy that generally discourages censuring of Abrahamic religions. Jacob de Roover demonstrated in his book Europe, India and the Limits of Secularism (2015) that secularism is a cultural construct of Protestant Christianity. Therefore, secular policies are often that of Christianity.

[iv] This issue is highlighted by Maria Wirth in her writings. One of her article was published in the inaugural issue of Dharma Today. See for example, https://mariawirthblog.wordpress.com/2016/07/18/a-reply-to-dr-zakir-naik/

[v] The phrase is a recent invention, first by Raja Rammohan Roy to our knowledge. The background is discussed in details by Rudra Pratap Chattopadhyaya, an undervalued writer, in his Bengali book “Ram Mohan ebang unish shataker dharma dushan”.

[vi] The nonsensical nature of this statement can be understood by perusal of Ram Swarup’s works, in particular, Understanding Islam through Hadis (1983) and Hindu View of Christianity and Islam (1993).

[1] The brahmins and the devatas both disputed on the need for animal sacrifice in yajna. The former group insisted on animal sacrifice but the latter group pointed out its redundancy. They came to Vasu, the King of Chedi, for arbitration. Vasu offered his verdict in favour of the latter group. This resulted in vegetable sacrifice in yajna instead of animal sacrifice. The brahmins got angry and cursed Vasu to being famished. The devatas came to his rescue and mandated the ritual of Vasudhara, wherein people offer rice and ghee to Vasu.

[1] The sixteenth chapter of the Gita makes a categorisation of Daivi and Asuric natures. This categorisation is very similar to the dharma-adharma categorisation.

[1] This law is not isolation but continuation of the secular policy that generally discourages censuring of Abrahamic religions. Jacob de Roover demonstrated in his book Europe, India and the Limits of Secularism (2015) that secularism is a cultural construct of Protestant Christianity. Therefore, secular policies are often that of Christianity.

[1] This issue is highlighted by Maria Wirth in her writings. One of her article was published in the inaugural issue of Dharma Today. See for example, https://mariawirthblog.wordpress.com/2016/07/18/a-reply-to-dr-zakir-naik/

[1] The phrase is a recent invention, first by Raja Rammohan Roy to our knowledge. The background is discussed in details by Rudra Pratap Chattopadhyaya, an undervalued writer, in his Bengali book “Ram Mohan ebang unish shataker dharma dushan”.

[1] The nonsensical nature of this statement can be understood by perusal of Ram Swarup’s works, in particular, Understanding Islam through Hadis (1983) and Hindu View of Christianity and Islam (1993).

The post Are Dharma and Religion the Same? appeared first on Dharma Today.

]]>The post The Indic Socio-Political Thinking appeared first on Dharma Today.

]]>Dharma tradition, one of the oldest social systems, has its own socio-political narrative. This narrative can, arguably, be identified with Indian nationalism which, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, was founded upon principles of Dharma. For instance, Sri Aurobindo[i]—in his Uttarpara speech in 1909—explained this connection:

When you go forth, speak to your nation always this word, that it is for the Sanatan Dharma that they arise, it is for the world and not for themselves that they arise. I am giving them freedom for the service of the world. When therefore it is said that India shall rise, it is the Sanatan Dharma that shall be great… When it is said that India shall expand and extend herself, it is the Sanatan Dharma that shall expand and extend itself over the world. It is for the Dharma and by the Dharma that India exists. I say that it is the Sanatan Dharma which for us is nationalism. This Hindu nation was born with the Sanatan Dharma, with it it moves and with it it grows. When the Sanatan Dharma declines, then the nation declines, and if the Sanatan Dharma were capable of perishing, with it the nation would perish. The Sanatan Dharma, that is nationalism.

Being inspired by this narrative, the Indian leaders in the early decades of twentieth century refused to acknowledge the western worldview and insisted on “swaraj” as the political goal rather than mere independence from British rule. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a famous nationalist of those times, who is often quoted as “Swaraj is my birth-right and I shall have it”, wrote a commentary on Gita, The Gita Rahasya, that explained dharma as the key to his socio-political narrative.

Being inspired by this narrative, the Indian leaders in the early decades of twentieth century refused to acknowledge the western worldview and insisted on “swaraj” as the political goal rather than mere independence from British rule. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a famous nationalist of those times, who is often quoted as “Swaraj is my birth-right and I shall have it”, wrote a commentary on Gita, The Gita Rahasya, that explained dharma as the key to his socio-political narrative.

“Swaraj” literally means Rule of the True Self. Dharma traditions acknowledge everyone’s True Self as self-same Pure Consciousness, often called the Atman.[ii] Generally, nationalism means devotion to one’s own motherland, acceptance of almost everything that belongs to the motherland, and at a minimum, mild rejection of everything that is foreign. However, Indic Nationalism is much deeper than this mere geographical notion of nationalism. Ram Swarup, a profound thinker of the twentieth century, expressed the essence of Indic Nationalism, which was narrated[iii] by Sita Ram Goel in his book How I Became Hindu: Swarup said, “But foreign should not be defined in geographical terms. Then it would have no meaning except territorial or tribal patriotism. To me that alone is foreign which is foreign to truth, foreign to Atman.”

The critics of nationalism often point out that being born in a land is not a matter of choice for a person. Therefore, being proud of one’s motherland is nothing extraordinary. Indic Nationalism is love for the motherland on account of a society that upholds the socio-political narrative of the Dharma Tradition in a continuous manner. And, there is every reason to be proud of being born in a society that has a continuity for thousands of years and has exclusively upheld the rule of the True Self. This ancientness and continuity of Indic civilisation makes it imperative for the members in the society to offer their duty to their society so that the reign of the True Self remains established in their society. This duty-mindedness is the ultimate essence and meaning of Indic Nationalism.

Historically, Indic Nationalism rarely called for territorial conquest but rather focussed on founding Dharma-based societies in other lands, as opposed to European origin nationalism. Even Han nationalism that emerged as the Chinese nation, has forever aspired for territorial conquest and annexing new lands. On the contrary, Indian kings always strived for inculcation of Dharma tradition among people of different lands without aspiring for military conquest and needless bloodshed.

In all probability, our Constitution-makers were not blind to this aspect of Dharma which is why they did not include the word “secular” in our nation’s constitution. This omission is likely on account of their understanding of the historic role of Dharma in facilitating governance and administration in India, which would be excluded on specification of the word “secular”. For instance, B. R. Ambedkar regarded Dharma as rational and relatively free of colonial bias. He was also supportive of a fundamental differentiation between Dharma and religion:

I regard the Buddha’s Dhamma to be the best. No religion can be compared to it. If a modern man who knows science must have a religion, the only religion he can have is the Religion of the Buddha. This conviction has grown in me after thirty-five years of close study of all religions. (Preface to The Buddha and His Dhamma)

The above statement clearly shows that Ambedkar was aware of scientific nature of Dhamma—the term for Dharma in Buddhist tradition—and made an analysis of different claims of truth without limiting himself to a faith based imposition.

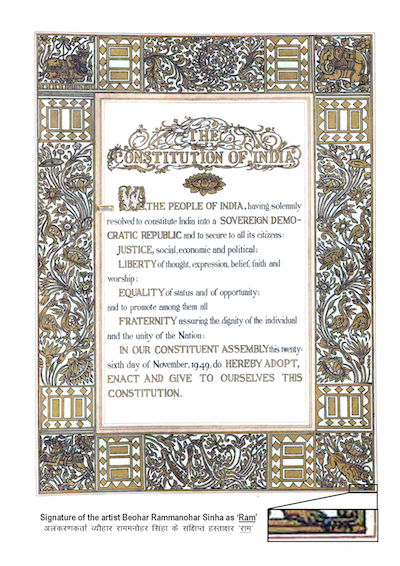

Not only Ambedkar, but the motifs drawn on the original copy of the Indian Constitution by Nandlal Bose and Beohar Rammanohar Sinha, have also been heavily inspired by the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and Sri Buddha apart from diverse historical figures.[iv] These motifs demonstrate that the Republic of India formed on November 26, 1949 was viewed as a civilizational continuity of our Dharma tradition rather than a new nation being forged.

Dharma and Secularism

Things, however, took a sharply radical turn in the post-independence era. The Indian elite have swallowed socio-political understanding of the western lands. Dharma is a word in Indic languages, which is non-translatable in English. Language is often said to be a matter of convention. Therefore, a particular culture may actually understand a word very differently than another one. For example, the word “secular” bears very different connotation to an Indian as opposed to a European. In Europe, a secular person will proactively fight for the right to criticise religious dogmas. Karl Marx said[v], “The criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism.” Interestingly, an Indian secular icon may very well consider criticism of a particular religion inherently as an anti-secular exercise.

Koenraad Elst provided a fine example in his book Decolonising the Hindu Mind (2001) in the backdrop of Indian Government’s banning of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. He cited Professor S. Guhan, a noted academician and secularist, who argued that banning any book that criticises Islam, is in the interest of secularism. This position, summarily speaking, describes the worldview of many of the Indian secularists, if not most.

When the same word, secular, can mean two diametrically opposite ideas under two cultural hegemonies, we understand the gravity of the problem of translation since the word

Dharma, has no synonym in English at all[vi]. This powerlessness of the highly-enriched English dictionary is a living testimony to West’s lack of exposure to an indigenous Dharma tradition for centuries. Since the West is almost ignorant about the Dharma traditions, naturally they have no understanding regarding socio-political institutions under the Dharma traditions.

To make matters worse, the Indian elite have followed the West in their education, in their socio-political institutions and in their narrative, thereby growing up without any knowledge about our Dharma traditions. When these elites formed their narrative about India, that narrative was devoid of any role for Dharma. The elite in India started learning about dharma in English which translated the word as “Religion”. In their colonised understanding, dharma became the primitive religion of India.

As the cultural roots of the elite have been cut off, they have become a susceptible target for a doctrine that least emphasises the importance of culture on human aspiration and human destiny. Marxism is exactly that very doctrine.[vii] Marxist sociology considers production as the base, and religion and culture as the superstructure—the base influences the superstructure but not vice versa. In other words, man’s emphasis should only be on factors of production, usually never on culture.

Dharma was, therefore, relegated to a very tertiary factor of the human civilisation, in that worldview. Moreover, Marxism, in particular its dialectics on Class Struggle, presents a linear history. Therefore, the contemporary technological inferiority of India was translated as perpetual technological backwardness of India. And, since factors of production essentially shape culture and religion under the Marxist paradigm, technological backwardness of India is translated into cultural inferiority of India. Dharma has become, to the colonised elite, India’s primitive religion whose demise per se would ensure India’s rejuvenation!

This linearity is utterly flawed as historically India was one of the most technologically advanced countries, till the first millennium AD, when the Dharma Tradition was strong in India. The reader may observe the European scientists’ recognition of Indian technological superiority by referring to Dharampal’s Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century. History of Indian Science and Technology (HIST) project by Rajiv Malhotra’s Infinity Foundation documented ancient Indian science and technology through many volumes.[viii]

Even though, a part of the elite—who are particularly not driven by any leftist ideological zeal against religion—acknowledge people’s right to practise dharma without being mocked, they consider it at best an exercise of personal freedom without any scope for socio-political narrative-making by dharma tradition. Consequently, Dharma tradition was left neglected dying a slow death.

Historically however, Indic education system, was centred around dharma: every Indian child used to start his writing in a temple a hundred years ago. But the Indian elite pursued separation of education and dharma as an ‘agenda’. Within a span of two to three generations, Indians forgot their own social and political institutions that have been sustained by dharma.

Decolonisation and Dharma Tradition

Decolonisation of India is yet to happen[ix]; but slowly and surely the colonised elite are being challenged in the realm of intellectual discourse. Post economic liberalisation, India has a sizeable English-educated middle class who are professionally successful. They are neither afraid of intellectual discourses in English (as was the case for many one or two generations ago) nor suffer from lack of information thanks to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) revolution. Some of these people are challenging the hegemony. Unless economic liberalisation is reversed, their voices can, no way, go down. Although most of the energy is being spent to call out only the ideological bankruptcy of the existing elite, eventually the focus will be on discovering Indic nationalism that is the Dharma tradition. Therefore, at this rate, the dharma tradition and its worldview will naturally be relevant again to Indian polity.

[1] The difference between Indian and Indic: The word Indian specifies something that belongs to the geographical boundary of India; Indic represents something that originated in India.

Ideas generally have no geographical boundary; hence many ideas that originate elsewhere in the world can find resonance among the Indians. For example, Nationalism is essentially a western concept but it appealed to a section of the Indian elite in the nineteenth century and twentieth century, which is why it is called Indian Nationalism.

Indic Nationalism means the notion of nationalism that originated in India and somewhat in variance with the western notion of nationalism.

[i] Aurobindo, Sri. Sanatan Dharma: Uttarpara Speech. Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram (1983). Also available at http://cw.routledge.com/textbooks/9780415485432/24.asp.

[ii] Buddhist traditions often consider everything as Anatma that is nullity as one’s True Self. Such a notion does not jeopardise the idea that everyone’s True Self is one and the same.

[iii] http://www.voiceofdharma.org/books/hibh/ch7.htm

[iv] http://www.opindia.com/2016/01/the-hidden-beauty-within-the-indian-constitution/

[v] A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Karl Marx available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/critique-hpr/intro.htm

[vi] Ram Swarup discussed the specific meaning of Indic words that goes beyond intellectual domain in his monumental work, The Word as Revelation . The problem of non-translatable Indic words is also elaborated well by Rajiv Malhotra in the fifth chapter of Being Different.

[vii] For a clear exposition of the Marxist arguments, one may consult A journey from the Volga to the Ganges, a fantastic story-telling by Rahul Sankrityayan.

[viii] http://rajivmalhotra.com/books/buy-infinity-books-india/.

[ix] Koenraad Elst’s Decolonising Hindu Mind discusses Indian elite’s cultural colonisation.

The post The Indic Socio-Political Thinking appeared first on Dharma Today.

]]>The post The Science of Dharma: Satya and Ahimsa appeared first on Dharma Today.

]]>Dharma could be defined[i] as the documented scientific path, which facilitates man’s progress to Absoluteness that is rooted in his True Self. The long-term peace of our mind is ensured if we move on the path to Absoluteness. Dharma can, therefore, also be called the ‘science’ of attaining peace. The use of the word science here may be puzzling for some, which has precisely been used to mark its distinction from a ‘faith’, the word that is typically used to describe a religion. The heart and soul of Dharma is not any faith based imposition but own calibrated realization. This has been termed as first-person empiricism by Rajiv Malhotra in his book Being Different (2011). First-person empiricism is the application of the scientific method where the mind is the lab, the intelligence is the scientist and the internal experiences are the subjects of experimentation and analysis.

Dharma: First-Person Empiricism Based Science

Every person’s mind is unique preventing one person from experiencing what another has already experienced. At the same time, universality of human experience is suggested too often. A reconciliation of these two conflicting notions is possible if different elements of the human mind are studied. Dharma is the scientific documentation of the human mind using the methodology of first-person empiricism so as to facilitate development of human consciousness.

Some of examples of Dharmic documentation of the human mind are: three-guna system, Pancha-Kosha System, Seven-Chakra System, 24-Tattvas of the Samkhya System. All these systems are very elaborate and can explain a great deal of human psychology.

Table: Science and Dharma

|

The Physical Science: Third Person Empiricism |

The Science of Dharma: First Person Empiricism |

|

Purpose: To discover laws and causal relationships in the physical world

|

Purpose: To discover laws and causal relationships in one’s inner faculty, typically called mind, further sub-divided into four parts of mana (mind), buddhi (intellect), aham (ego) and chitta (sub-conscious) by the dharma practitioners. |

|

Philosophy: 1. Propose a falsifiable hypothesis. 2. Prepare suitable instruments. 3. Run an experiment. 4. Observe to conclude about a physical law. |

Philosophy: 1. Propose a falsifiable hypothesis, which means faiths with non-observable outcomes are not allowed. 2. Cultivate a calm inner existence through rituals involving body and mind. 3. Run an inner experiment (tapasya). 4. Observe to conclude about a law on inner faculty. |

Source: Author

The Table above contrasts physical science and Dharma.

The first step talks about a falsifiable hypothesis, which Karl Popper clarifies, is the basic prerequisite of all science. It must be possible to disprove the proposed hypothesis. Most religions would not qualify to be a Dharma in light of the requirement of the testability of the hypothesis. If a theory (a religion) promises its adherents a stay in heaven on account of a particular belief or faith, then such a promise is not testable for an ordinary human being, and hence that theory cannot be a part of the Dharma tradition.

In an experiment involving a hypothesis of the physical world, the observer is not involved in the process. Therefore, after preparing the necessary instruments, the experiment is set in motion and the outcome is noted. In the first-person empiricism, the task of the observer is much more complex. The inner experiment involves the observer. Therefore, it is not easy for the observer to decide what is actually happening. The second step talks about preparing the observer so as to conduct the experiment. If the observer’s day-to-day mind is stable, then and only then, one can assess the impact of the inner experiment.

In an experiment involving a hypothesis of the physical world, the observer is not involved in the process. Therefore, after preparing the necessary instruments, the experiment is set in motion and the outcome is noted. In the first-person empiricism, the task of the observer is much more complex. The inner experiment involves the observer. Therefore, it is not easy for the observer to decide what is actually happening. The second step talks about preparing the observer so as to conduct the experiment. If the observer’s day-to-day mind is stable, then and only then, one can assess the impact of the inner experiment.

How can mental stability be ensured? Traditionally, among many other methods, practice of rituals has been quite effective. Let me elaborate with a concrete example. For cultivating a calm inner existence, daily practice of Sandhya-upasana was first suggested by in the Grihyasutras[ii] and then in other Dharma texts. It is important to note here that these suggestions have been put forward based on the experiences of the Dharma-practitioners. The practitioners are required to perform Sandhya-upasana daily to calm their inner faculty, which needs to be accompanied with yoga and ethics.

In the third step, known as Tapasya, a first-person empiricist applies that impetus to himself / herself in addition to pursuit of daily routine that includes Sandhya-upasana, and observes the outcome. This helps in understanding the effect of any external or internal impetus, which is the fourth step. For a ritual to achieve validity and acceptance, it has to pass through this methodology.

In the third step, known as Tapasya, a first-person empiricist applies that impetus to himself / herself in addition to pursuit of daily routine that includes Sandhya-upasana, and observes the outcome. This helps in understanding the effect of any external or internal impetus, which is the fourth step. For a ritual to achieve validity and acceptance, it has to pass through this methodology.

Now supposing we want to verify the effect of a particular chanting on our psychology, we must first practise the associated rituals for a long time to stabilise our mind and then perform this chanting for some time to detect its effect on our psychology. Some mantras may increase our stamina, some may increase peace of mind, some may make us more balanced, some may increase our compassion; and yet some may increase our sexual prowess and so on. It may depend upon which of our nerves and which part of our brain are activated by the chanting of that particular mantra.[iii] This can be detected scientifically by this methodology of first-person empiricism.

Rishis as First-Person Empiricists

Rishis as First-Person Empiricists

Rishis are believed to be accomplished first-person empiricists who discovered the most beneficial mantras. Those mantras were codified in the form of the Vedas. Rishis have been credited the invention of the language of Sanskrit, which many believe is the natural language for human beings. I quote the Rig-Veda (10.71 Jnanam, verses 1-3) that has poetically described this phenomenon (Translation by Ralph T.H. Griffith):

When men, Bṛhaspati, giving names to objects, sent out Vāk’s first and earliest utterances, All that was excellent and spotless, treasured within them, was disclosed through their affection.

(2) Where, like men cleansing corn-flour in a cribble, the wise in spirit have created language, Friends see and recognize the marks of friendship: their speech retains the blessed sign imprinted.

(3) With sacrifice the trace of Vāk they foIlowed, and found her harbouring within the Ṛṣis.

They brought her, dealt her forth in many places: seven singers make her tones resound in concert.

Dharma is Practice

Our definition of Dharma clarifies a number of points. First and foremost, dharma does not exist in mere utterance of high-sounding philosophy or thought-experiment based understandings, which may very well be either figments of one’s mind or superficial thinking without any relevance to truth and reality. Dharma is characterised by scientific practice. Unfortunately, scientific practice based Dharma tradition is a rarity, now. Dharma, to a layman, is often synonymous to high-sounding words on unreal nature of the universe, and inaction, which the reader can perceive to be a non-desirable outgrowth of Hinduism.

Dharma Is Decentralised by Nature

Dharma Is Decentralised by Nature

Next, our definition explains why the focus of the Dharma tradition was never the ‘Book that is an absolute priority for a faith based religion. Dharma-practitioners attach utmost importance to the direct experience (anubhava) obtained through pursuit of the above described scientific methodology and words of the persons who received such anubhava.. This is suggestive of decentralised nature of dharma in contrast to the centralised Book-based religions.

Some books that narrate anubhavas from higher stages of consciousness, or suggest the most beneficial action-policy or illustrate character of Great Dharma-practitioners, are revered in the Dharma tradition such as the Vedas, the Gita, The Ramayana, The Mahabharata, The Jataka Tales and the like. However, they act merely as a benchmark for examination of practitioner’s own anubhava rather than being the final revelation.

Definition of the Dharma tradition

First-person-empiricism which is called dharma, has given rise to an understanding of codes of human living—individual as well as collective. Such living when practiced individually and collectively, gives rise to, what we call, the Dharma tradition. Many such traditions have existed in India for ages.

Satya and Ahimsa: Ethical Foundations of Dharma

Satya and Ahimsa: Ethical Foundations of Dharma

Two human traits are central to the Dharma tradition. We know that human brain is generally bi-functional. The left brain is associated with knowledge and the right brain is intrinsically linked to activity: Satya (real; truth) is linked to cultivation of knowledge and ahimsa (a non-translatable word, often wrongly translated as non-violence) to human activity. Dharma acknowledges that an absolute common level of reality is an ‘impossibility’, as everyone’s reality may depend to a great extent on his/ her perspective.[iv] However, this is different from the post-modernist standpoint that ‘anything’ can pass of as truth, including someone’s convenient and self-deceived lie. Satya comes with an uncompromising recommendation: we should move from unreal to real.

Similarly, Ahimsa is not physical non-violence, which is again almost impossible on account of our physical existence. Our biological existence, at a minimum, demands food, which, almost always, means harming some conscious entity. Ahimsa means a policy of action that aims to negate himsa (violence) in the world. If the origin of that himsa is practitioner’s own mind, he must practise physical (and mental) non-violence; if the violence is rooted in someone else’s mind, a practitioner must do whatever is necessary to stop that someone else’s aggression.

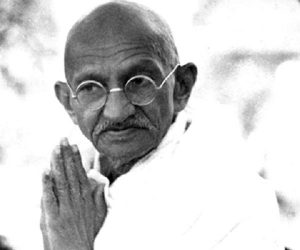

This is markedly different compared to Mahatma Gandhi’s interpretation of ahimsa as non-violence. What Gandhi proposed was in line with the Christian[v] idea of pacifism. George Orwell presents[vi] the dilemma in the context of Hitler’s aggression during the World War II toward the Jews:

“What about the Jews? Are you prepared to see them exterminated? If not, how do you propose to save them without resorting to war?” … According to Mr. Fischer, Gandhi’s view was that the German Jews ought to commit collective suicide, which “would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler’s violence.” After the war he justified himself: the Jews had been killed anyway, and might as well have died significantly.

Gandhi prescribed the Jews to commit collective suicide on the face of Hitler’s violence. This Gandhian attitude is not ahimsa but actually himsa. He rightfully acknowledged Hitler as the source of himsa. However, instead of negation of this himsa by countering Hitler in one’s own capacity, he prescribed allowing Hitler a free hand which meant augment in himsa.

Gandhi prescribed the Jews to commit collective suicide on the face of Hitler’s violence. This Gandhian attitude is not ahimsa but actually himsa. He rightfully acknowledged Hitler as the source of himsa. However, instead of negation of this himsa by countering Hitler in one’s own capacity, he prescribed allowing Hitler a free hand which meant augment in himsa.

Ahimsa is Not Pacifism: Rama, Krishna and Buddha

The natural inclination to dialogue and tolerance by Dharma-practitioners does not imply any tolerance for those who, for their own hedonistic purposes, intrude on others. On the contrary, the highest principal of Dharma demands conscious action against those intruders. Dharma prescribes stern action —even death sentence depending on the extent of intrusion —against those aggressors who are not willing to amend themselves to voices of reason and conscience.

Manu described this idea categorically (Chapter VIII: verse 350-351):

One may slay without hesitation an aggressor [âtatâyin] who approaches,, whether (he be one’s) teacher, a child or an aged man, or a Brahmana deeply versed in the Vedas.

By killing an aggressor [âtatâyin] the slayer incurs no guilt, whether (he does it) publicly or secretly; in that case fury recoils upon fury.

The definition of atatayin has been put forth by Vasishtha Samhita (Chapter III: 11):

An incendiary, likewise a poisoner, one who holds a weapon in his hand (ready to kill), a robber, he who takes away land, and he who abducts (another man’s) wife, these six are called assassins (âtatâyin).

Sri Rama and Sri Krishna are traditionally hailed as great practitioners of Dharma but lived their life through exemplary opposition to the aggressors. They were unforgiving towards aggressors. Sri Buddha was against needless bloodshed but never appeared as a Pacifist. “Buddhist values are not simply pacifist, and Buddhist scripture and legend inform us that Avalokiteśvara [the deva of compassion]readily takes a warrior’s form when needed and supports the warfare of righteous kings.”[vii]

Ahimsa is not Passivity

Ahimsa is not Passivity

In spite of the general liberal attitude of Dharma-tradition, it does not stand for any neutrality towards the intolerant. This paradox arises from the fact that if the intolerant is tolerated, the intolerant devours the tolerant to remain the only voice. Therefore, tolerance for the intolerance is logically inconsistent. Rather the principle of ahimsa demands that a Dharma-practitioner must stop the intolerant to flourish at all costs. This is a principle which is easy to preach but perhaps most difficult to practise. It takes enormous amount of courage, determination and sacrifice to take up arms for the sole cause of practising ahimsa, without expecting any reward in this world. A true Dharma-based practice must endow the practitioner with such courage, determination, sacrifice and respect for Ahimsa.

[i] The definition has been provided by Swami Satyananda Saraswati who was a first-person-empiricist, in his Bengali work “Kramavikasher Pathe” (1934, The Path to Evolution).

[ii] The Grihya Sutras are texts containing information regarding Vedic domestic rites and rituals meant for the householders. The Grihya Sutras as their name suggests deal with domestic rituals such as conception, birth, initiation (upanayanam), marriage, death etc. Names of some of the Grihya Sutras are Sankhyayana-Grihya-sutra, Asvalayana-Grihya-sutra, Paraskara Grihya-sutra and Khadia Grihya sutra.

[iii] Kramavikasher Pathe, Chapter 7.

[iv] In the popular culture, Akira Kurosawa’s movie Rashomon is considered a masterpiece for elucidating the idea of relative reality

[v] Shanmukh, Saswati Sarkar, Divya Kumar Soti and Dikgaj, Was Gandhi a Christian in faith and Hindu in name?

[vi] Reflections on Gandhi, George Orwell. Available at http://www.orwell.ru/library/reviews/gandhi/english/e_gandhi

[vii] It’s not so strange for a Buddhist to endorse killing, Stephen Jenkins. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2011/may/11/buddhism-bin-laden-death-dalai-lama

The post The Science of Dharma: Satya and Ahimsa appeared first on Dharma Today.

]]>