International trade has existed since time immemorial but intercultural exchange was passive at best and engaged by the highest echelons of society. The exchange only trickled in because of the time, energy and resources it took for knowledge and artifacts to travel distances.

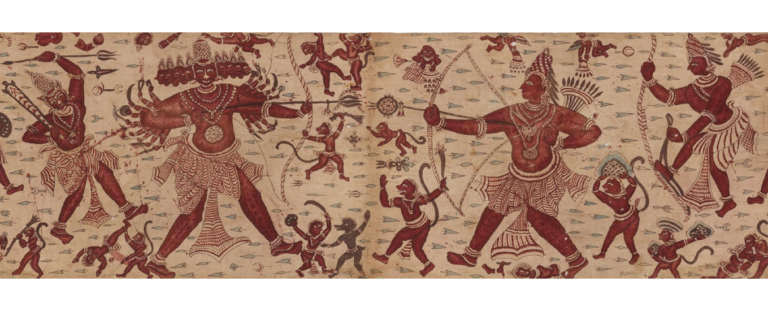

The most expedient way, in a time of limited technology, to absorb entire lots of people into the dominant societies’ civilizational fishnet was by hostile takeover – war. The invaded and defeated people were then relatively, quickly assimilated, into the ways and norms of the invaders. Religions, commerce, social standards and cultural ethos were all unceremoniously uprooted and discarded, until only tattered ghosts of the past were left to haunt the captured generations with the life that was. From Genghis Khan to Alexander the Great, history is replete with examples of civilizational hijacking.

Mind Games

However, as technology advanced and globalization took center stage, nations realized that the options on the table for domination had expanded. War was not the necessary or even preferred means to capture the minds of the ‘other’ masses. Through modern statecraft, mass media and global accessibility to citizens of the world, one nation or region could hold another hostage economically, socially and/ or culturally, without any overt military gestures. Appropriate to the Information Age, a new kurukshetra or a battlefield has emerged where the front is the mind and our cultural identity the prize.

One of the most sought after prizes over the last fifteen hundred years has been the Indian civilization. In almost every category of value, India has had something to offer its people and the world at large. Over the last three centuries, the latest incarnation of appropriation of Indian cultural has been led by the Western intelligentsia.

Indologists Rising

As far back as Sir William Jones of the eighteenth century, Indologists have played a complex game of praising and admonishing the traditions of dharma. No true intellectual can honestly ignore the broad range of profound metaphysical and existential truths that permeate the intellectual, social and personal arenas of the dharma-based societies. Yet these philosophies and their embodied manifestations were categorically different enough from the religions and philosophies of the West that the dharma traditions were equally targets of ridicule, appropriation, misinterpretation and even destruction.

Dharmic intellectuals like Sri Aurobindo, Swami Vivekananda and Sita Ram Goel identified and outlined this destructive journey of the Western elites and worked to stand up for their cultural identity.

As a poignant example, in his Indian Spirituality and Life, Sri Aurobindo exclaims:

Here is the first baffling difficulty over which the European mind stumbles; for it finds itself unable to make out what Hindu religion is…How can there be a religion which has no rigid dogmas demanding belief on pain of eternal damnation, no theological postulates, even no fixed theology, no credo distinguishing it from antagonistic or rival religions? How can there be a religion which has no papal head, no governing ecclesiastic body, no church, chapel or congregational system, no binding religious form of any kind obligatory on all its adherents, no one administration and discipline? For the Hindu priests are mere ceremonial officiants without any ecclesiastical authority or disciplinary powers and the Pundits are mere interpreters of the Shastra, not the lawgivers of the religion or its rulers. How again can Hinduism be called a religion when it admits all beliefs, allowing even a kind of high-reaching atheism and agnosticism and permits all possible spiritual experiences, all kinds of religious adventures?

A Not So Intelligent Fixation

The Battle for Sanskrit, the latest book by Hindu intellectual and cultural strategist Rajiv Malhotra, has immersed many Hindus into the crosshairs of Western thinkers. Many leading Western academics have interpreted the dharmic knowledge systems with lens’ outside the confines and frameworks of the dharmic traditions themselves. By such interpretation governments, institutions and the masses have been categorically misinformed about the very nature of dharma and its manifestation in India and beyond.

Sheldon Pollock, the primary target of intellectual critique in Malhotra’s book, is considered by many as the leading Sanskrit scholar and Indologist of our times. Upon further exploration of Sheldon Pollock’s perspectives, a particular video (http://video.scroll.in/804595/watch-sheldon-pollock-answering-his-own-question-what-is-indian-knowledge-good-for) was unearthed, where he was speaking to Indians in Mumbai, India in 2014. Some of his views struck a nerve.

In his talk and in line with many of his Indologist ancestors, there were several assertions by Pollock, albeit craftily made, that run counter to the ethos of Sanskrit and sanskriti – dharmic living.

We do not study ancient Indian past to find the cure for cancer in a Vedic text. There is no cure for cancer in a Vedic text, there’s no recipe for cold fusion in the Veda. Knowing something about the past is radically non-instrumental if I can put it that way.

Sanskrit As It Is

Sanskrit grammar is condensed into the minimal amount of words as possible for a reason. The codified language, where a single word can have innumerable meanings, keeps the door open for innovation in understanding and application.

For instance, the Sanskrit word atma can mean the self, one’s body, one’s mind, one’s spiritual identity, a sense of one’s identity, all of the above at the same time or some combination of the above. When placed in a Sanskrit phrase, the context will help one to unravel its intended meaning. But the most authoritative translators who are spiritually mature and in tune with standards of interpretation have the clearest purview into unlocking the secret behind every word.

All this means that Sanskrit is designed to withstand shifts in time and culture. While context helps, it is not bound to context as a vast array of Sanskrit terms, especially those found in sastra (spiritual texts of dharma), have built in meta meanings that may have more relevance in one era than another. Therefore, claiming that Sanskrit is a relic of the past with no relevance to the present and especially the future is to belittle its intrinsic truth.

The Realms of Consciousness

Krishna says in the Bhagavad Gita that individuals and societies succumb to the lower realms of consciousness as and when they cannot unearth the eternal and divine aspects of things. Their perception of the world is thus filtered by this consciousness. But the higher your consciousness rises the more you are able to perceive the very filters themselves and ultimately see beyond them. This state cannot be achieved through empirical means alone as it requires commitment to the spiritual practices embedded in the very traditions one is seeking to understand.

This is explained repeatedly throughout the Upanishads and Puranas yet routinely ignored by secular enthusiasts and academics. The reason is they have to ignore it (and systematically so) in order to preserve the ‘integrity’ of their historical consciousness. Historical consciousness refers to the sequencing and piecing together of tangible and intangible evidence of the Western and Abrahamic systems of thought and faith. It gives rise to endless dogmas and an impulse to destroy all elements of their own or others’ cultures that would sabotage this way of living and thinking. Hence, for them, denying Sanskrit’s inherent and independent sacredness is a categorical imperative.

Don’t Look Back

Finally, the Western discomfort with the past is something to be deeply analyzed. For the West, the past is something to be overcome and generally associated with our less evolved states of being.

There is no better evidence of this than the West’s obsession with progress. While there is no denying that progress is something to be coveted for us all, there is an assumption in the collective Western consciousness that all things not new are less good than those that are. This may be partially true for areas like technology but sets a scary stage when applied to social affairs, politics and personal development.

Infinity and Beyond

Such thinking, a byproduct of a historical consciousness that anchors itself to the realm of the finite, is dangerously limiting. The Abrahamic traditions, of which the most notable Western Indologists ascribe to, especially commit to a fixed point in time and space where the genesis of all creation including their own existence has come to be. How then can such thinkers be handed the keys to the matters of the infinite?

Superimposing this paradigm onto the traditions of Dharma relegates Sanskrit and sanskriti, by association, to an entirely secular experience riddled with worldly motives, as Pollock exclaims, and not something that descends from and is imbued with divinity. Not something that represents the experience of hundreds of millions in the past, in the present and the centuries to come.