My book (Being Different) brings to the foreground some fundamental differences between Indian and Western civilizations, and explores at length the spiritual, metaphysical, philosophical and historical basis for such differences. I argue, that to gloss over these differences, reveals a dismal lack of civilizational self-awareness and wishful thinking on the part of Westerners, and low self-esteem by Indians resulting in part of an education system that seems to be still fulfilling the mandates of colonial educators.

Dharmic leadership too should be faulted for this when they are disinclined to embark on a serious comparative study of the West and India. Laziness, the loss of the culture of scholarship, research and contemplation that once defined India, superciliousness (“the truth is with us, so why should we study others”) and the sheer challenge of confronting the West are some of the reasons for this. The discomfort and loss of easy Western discipleship that such a study with its resulting assertiveness would bring is another reason for the prevailing “we are all the same” attitude among the retinue of Indian gurus who should know better. Yet, without the search, serious study and discovery of one’s own authenticity, Indians will remain colonized – in spirit and intellect if not physically. A further travesty is that Indians, blind to and kept from the riches of their heritage, find themselves in the sorry state of flocking to Western appropriators of their legacy, unaware that it is they who really are the proud legatees of that knowledge.

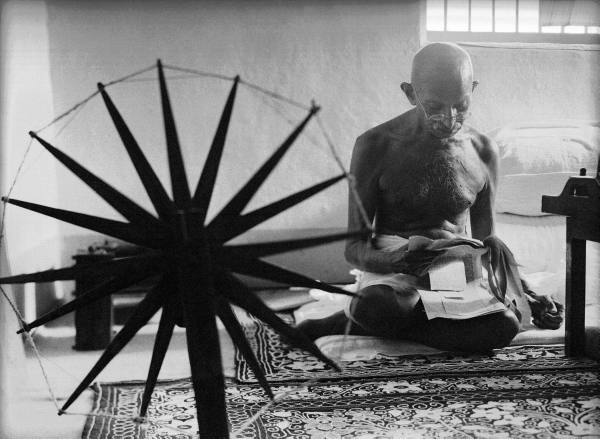

But there are rare exemplars of the power of authenticity and self-knowledge. Mahatma Gandhi, at the height of colonial rule in India, had the audacity to assert his dharmic differences firmly but without chauvinism. He was steeped in Indian cultural habits and experimented with dharma all his life. Speaking in very simple and precise terms, he managed to alter the course of world history. After abandoning his early experiments to “become a gentleman” in the mold of the Englishmen who ruled over the sub-continent, Gandhi found his own personal liberation in embracing wholeheartedly the manner, lifestyle, dress and idiom of his fellow countrymen. Gandhi understood early on in his life’s work, that India’s independence could be won only after the structures of engagement, the very terms of the discourse between the colonizer and the colonized, were altered and reversed, such that Indians would regain their native intelligence, skills and cultural power. He fought against not only the physical presence of the Europeans in India but their violence against the native religion, language, customs, symbols and way of life of Indian people. These had served historically to nourish, empower and strengthen Indians in their long history. Gandhi once again, wanted to harness this very shakti for the freedom of his people.

As the leader of India’s freedom movement, Gandhi relied greatly on the use of Sanskrit words to give voice to India’s struggle and demands. Words like “satyagraha”, “swadeshi”, “swaraj”, “ahimsa”, “sva-dharma” became an integral part of the lexicon of the Indian freedom struggle. By using these words and not their English equivalents, Gandhi preserved the complete range of their complex meaning, their dharmic origins and their cultural context. Rather than relying on the English language, India’s struggle against the English was expressed in a language that was culturally resonant, making it all the more meaningful and empowering to those engaged in it. Thus, India’s freedom fight wasn’t just a struggle but a “truth-struggle” (“Satya-graha”). Such a truth struggle therefore could have no place for violence (a falsity) but would have to be conducted in a manner that befit the bearers of truth. Moreover, the full meaning of “satya” includes not just the concept of truth but the constant striving for it, something to be aspired for and eternally engaged in. The hyphenation of truth and struggle, seemingly odd perhaps in English to describe an independence movement, is natural when extrapolated from the original Sanskrit language. “Swaraj” is not just freedom but “self-rule”. By using the term “swaraj”, Gandhi spoke not only for the entire nation’s freedom from British rule but also encompassed the right to self-determination by all of India’s diverse communities, particularly those in rural and agrarian India. Gandhi’s self-rule wasn’t just the rule of the majority but a truly pluralistic self-regulation by all of India’s peoples. To that end, he advocated a traditional, decentralized (“panchayat”) system of governance for India, quite unlike the top-down colonial administration of the British.

Further, the meaning of “swaraj” also includes freedom from the emotions, desires and compulsions that haunt our inner being. Complete “swaraj” was more than political independence and included liberation from one’s psychological bondage. Gandhi always saw India’s freedom struggle as one intertwined with the spiritual struggle of its citizens.

The term “ahimsa” is more than non-violence. “Himsa” translates to “harm” and “ahimsa” is not just non-violence, a narrow and incomplete translation, but more accurately “non-harming”. It wasn’t enough for Gandhi to not physically kill in the freedom struggle. The good fight necessarily precluded all forms of harm – cultural genocide, environmental degradation, animal slaughter and even the psychological humiliation of others. When Gandhi used the term “swadeshi” or “from the soil”, to alter the buying habits of Indians, he meant not only the boycott of English manufactured products, a key weapon of domination in the colonial economy, but also the idea of consuming locally produced goods and seasonal produce. These he saw as critical to maintaining the health and vibrancy of local Indian communities and farmers. Swadeshi also means native frameworks of thinking, native language, dress and a sense of identity.

Gandhi’s life illustrates many key points that I make in my book and in my own personal journey. I continue to draw great inspiration from him. His “purva-paksha” of the West was challenging and audacious. His use of non-translatable Sanskrit words to articulate India’s freedom struggle was a strategic way of managing and owning the discourse surrounding his culture. His way of life demonstrated how differences may be asserted constructively. India’s independence was a historical event of the twentieth century which validated that cultures and civilizations must refuse to let their selfhood get digested by a predator, and that the audacity to be non-digestible must prevail.