Acknowledgement: I sincerely thank Kaal Chiron (twitter handle @Kal_Chiron) for his inputs.

Dharma could be defined[i] as the documented scientific path, which facilitates man’s progress to Absoluteness that is rooted in his True Self. The long-term peace of our mind is ensured if we move on the path to Absoluteness. Dharma can, therefore, also be called the ‘science’ of attaining peace. The use of the word science here may be puzzling for some, which has precisely been used to mark its distinction from a ‘faith’, the word that is typically used to describe a religion. The heart and soul of Dharma is not any faith based imposition but own calibrated realization. This has been termed as first-person empiricism by Rajiv Malhotra in his book Being Different (2011). First-person empiricism is the application of the scientific method where the mind is the lab, the intelligence is the scientist and the internal experiences are the subjects of experimentation and analysis.

Dharma: First-Person Empiricism Based Science

Every person’s mind is unique preventing one person from experiencing what another has already experienced. At the same time, universality of human experience is suggested too often. A reconciliation of these two conflicting notions is possible if different elements of the human mind are studied. Dharma is the scientific documentation of the human mind using the methodology of first-person empiricism so as to facilitate development of human consciousness.

Some of examples of Dharmic documentation of the human mind are: three-guna system, Pancha-Kosha System, Seven-Chakra System, 24-Tattvas of the Samkhya System. All these systems are very elaborate and can explain a great deal of human psychology.

Table: Science and Dharma

|

The Physical Science: Third Person Empiricism |

The Science of Dharma: First Person Empiricism |

|

Purpose: To discover laws and causal relationships in the physical world

|

Purpose: To discover laws and causal relationships in one’s inner faculty, typically called mind, further sub-divided into four parts of mana (mind), buddhi (intellect), aham (ego) and chitta (sub-conscious) by the dharma practitioners. |

|

Philosophy: 1. Propose a falsifiable hypothesis. 2. Prepare suitable instruments. 3. Run an experiment. 4. Observe to conclude about a physical law. |

Philosophy: 1. Propose a falsifiable hypothesis, which means faiths with non-observable outcomes are not allowed. 2. Cultivate a calm inner existence through rituals involving body and mind. 3. Run an inner experiment (tapasya). 4. Observe to conclude about a law on inner faculty. |

Source: Author

The Table above contrasts physical science and Dharma.

The first step talks about a falsifiable hypothesis, which Karl Popper clarifies, is the basic prerequisite of all science. It must be possible to disprove the proposed hypothesis. Most religions would not qualify to be a Dharma in light of the requirement of the testability of the hypothesis. If a theory (a religion) promises its adherents a stay in heaven on account of a particular belief or faith, then such a promise is not testable for an ordinary human being, and hence that theory cannot be a part of the Dharma tradition.

In an experiment involving a hypothesis of the physical world, the observer is not involved in the process. Therefore, after preparing the necessary instruments, the experiment is set in motion and the outcome is noted. In the first-person empiricism, the task of the observer is much more complex. The inner experiment involves the observer. Therefore, it is not easy for the observer to decide what is actually happening. The second step talks about preparing the observer so as to conduct the experiment. If the observer’s day-to-day mind is stable, then and only then, one can assess the impact of the inner experiment.

In an experiment involving a hypothesis of the physical world, the observer is not involved in the process. Therefore, after preparing the necessary instruments, the experiment is set in motion and the outcome is noted. In the first-person empiricism, the task of the observer is much more complex. The inner experiment involves the observer. Therefore, it is not easy for the observer to decide what is actually happening. The second step talks about preparing the observer so as to conduct the experiment. If the observer’s day-to-day mind is stable, then and only then, one can assess the impact of the inner experiment.

How can mental stability be ensured? Traditionally, among many other methods, practice of rituals has been quite effective. Let me elaborate with a concrete example. For cultivating a calm inner existence, daily practice of Sandhya-upasana was first suggested by in the Grihyasutras[ii] and then in other Dharma texts. It is important to note here that these suggestions have been put forward based on the experiences of the Dharma-practitioners. The practitioners are required to perform Sandhya-upasana daily to calm their inner faculty, which needs to be accompanied with yoga and ethics.

In the third step, known as Tapasya, a first-person empiricist applies that impetus to himself / herself in addition to pursuit of daily routine that includes Sandhya-upasana, and observes the outcome. This helps in understanding the effect of any external or internal impetus, which is the fourth step. For a ritual to achieve validity and acceptance, it has to pass through this methodology.

In the third step, known as Tapasya, a first-person empiricist applies that impetus to himself / herself in addition to pursuit of daily routine that includes Sandhya-upasana, and observes the outcome. This helps in understanding the effect of any external or internal impetus, which is the fourth step. For a ritual to achieve validity and acceptance, it has to pass through this methodology.

Now supposing we want to verify the effect of a particular chanting on our psychology, we must first practise the associated rituals for a long time to stabilise our mind and then perform this chanting for some time to detect its effect on our psychology. Some mantras may increase our stamina, some may increase peace of mind, some may make us more balanced, some may increase our compassion; and yet some may increase our sexual prowess and so on. It may depend upon which of our nerves and which part of our brain are activated by the chanting of that particular mantra.[iii] This can be detected scientifically by this methodology of first-person empiricism.

Rishis as First-Person Empiricists

Rishis as First-Person Empiricists

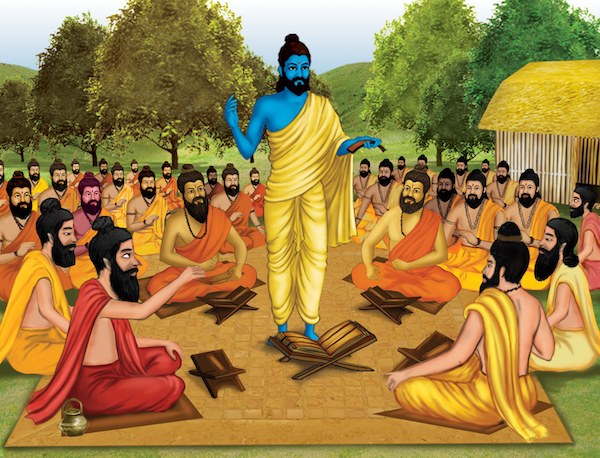

Rishis are believed to be accomplished first-person empiricists who discovered the most beneficial mantras. Those mantras were codified in the form of the Vedas. Rishis have been credited the invention of the language of Sanskrit, which many believe is the natural language for human beings. I quote the Rig-Veda (10.71 Jnanam, verses 1-3) that has poetically described this phenomenon (Translation by Ralph T.H. Griffith):

When men, Bṛhaspati, giving names to objects, sent out Vāk’s first and earliest utterances, All that was excellent and spotless, treasured within them, was disclosed through their affection.

(2) Where, like men cleansing corn-flour in a cribble, the wise in spirit have created language, Friends see and recognize the marks of friendship: their speech retains the blessed sign imprinted.

(3) With sacrifice the trace of Vāk they foIlowed, and found her harbouring within the Ṛṣis.

They brought her, dealt her forth in many places: seven singers make her tones resound in concert.

Dharma is Practice

Our definition of Dharma clarifies a number of points. First and foremost, dharma does not exist in mere utterance of high-sounding philosophy or thought-experiment based understandings, which may very well be either figments of one’s mind or superficial thinking without any relevance to truth and reality. Dharma is characterised by scientific practice. Unfortunately, scientific practice based Dharma tradition is a rarity, now. Dharma, to a layman, is often synonymous to high-sounding words on unreal nature of the universe, and inaction, which the reader can perceive to be a non-desirable outgrowth of Hinduism.

Dharma Is Decentralised by Nature

Dharma Is Decentralised by Nature

Next, our definition explains why the focus of the Dharma tradition was never the ‘Book that is an absolute priority for a faith based religion. Dharma-practitioners attach utmost importance to the direct experience (anubhava) obtained through pursuit of the above described scientific methodology and words of the persons who received such anubhava.. This is suggestive of decentralised nature of dharma in contrast to the centralised Book-based religions.

Some books that narrate anubhavas from higher stages of consciousness, or suggest the most beneficial action-policy or illustrate character of Great Dharma-practitioners, are revered in the Dharma tradition such as the Vedas, the Gita, The Ramayana, The Mahabharata, The Jataka Tales and the like. However, they act merely as a benchmark for examination of practitioner’s own anubhava rather than being the final revelation.

Definition of the Dharma tradition

First-person-empiricism which is called dharma, has given rise to an understanding of codes of human living—individual as well as collective. Such living when practiced individually and collectively, gives rise to, what we call, the Dharma tradition. Many such traditions have existed in India for ages.

Satya and Ahimsa: Ethical Foundations of Dharma

Satya and Ahimsa: Ethical Foundations of Dharma

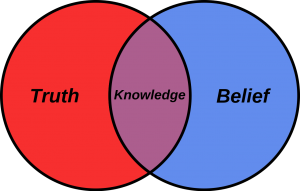

Two human traits are central to the Dharma tradition. We know that human brain is generally bi-functional. The left brain is associated with knowledge and the right brain is intrinsically linked to activity: Satya (real; truth) is linked to cultivation of knowledge and ahimsa (a non-translatable word, often wrongly translated as non-violence) to human activity. Dharma acknowledges that an absolute common level of reality is an ‘impossibility’, as everyone’s reality may depend to a great extent on his/ her perspective.[iv] However, this is different from the post-modernist standpoint that ‘anything’ can pass of as truth, including someone’s convenient and self-deceived lie. Satya comes with an uncompromising recommendation: we should move from unreal to real.

Similarly, Ahimsa is not physical non-violence, which is again almost impossible on account of our physical existence. Our biological existence, at a minimum, demands food, which, almost always, means harming some conscious entity. Ahimsa means a policy of action that aims to negate himsa (violence) in the world. If the origin of that himsa is practitioner’s own mind, he must practise physical (and mental) non-violence; if the violence is rooted in someone else’s mind, a practitioner must do whatever is necessary to stop that someone else’s aggression.

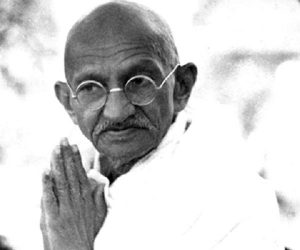

This is markedly different compared to Mahatma Gandhi’s interpretation of ahimsa as non-violence. What Gandhi proposed was in line with the Christian[v] idea of pacifism. George Orwell presents[vi] the dilemma in the context of Hitler’s aggression during the World War II toward the Jews:

“What about the Jews? Are you prepared to see them exterminated? If not, how do you propose to save them without resorting to war?” … According to Mr. Fischer, Gandhi’s view was that the German Jews ought to commit collective suicide, which “would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler’s violence.” After the war he justified himself: the Jews had been killed anyway, and might as well have died significantly.

Gandhi prescribed the Jews to commit collective suicide on the face of Hitler’s violence. This Gandhian attitude is not ahimsa but actually himsa. He rightfully acknowledged Hitler as the source of himsa. However, instead of negation of this himsa by countering Hitler in one’s own capacity, he prescribed allowing Hitler a free hand which meant augment in himsa.

Gandhi prescribed the Jews to commit collective suicide on the face of Hitler’s violence. This Gandhian attitude is not ahimsa but actually himsa. He rightfully acknowledged Hitler as the source of himsa. However, instead of negation of this himsa by countering Hitler in one’s own capacity, he prescribed allowing Hitler a free hand which meant augment in himsa.

Ahimsa is Not Pacifism: Rama, Krishna and Buddha

The natural inclination to dialogue and tolerance by Dharma-practitioners does not imply any tolerance for those who, for their own hedonistic purposes, intrude on others. On the contrary, the highest principal of Dharma demands conscious action against those intruders. Dharma prescribes stern action —even death sentence depending on the extent of intrusion —against those aggressors who are not willing to amend themselves to voices of reason and conscience.

Manu described this idea categorically (Chapter VIII: verse 350-351):

One may slay without hesitation an aggressor [âtatâyin] who approaches,, whether (he be one’s) teacher, a child or an aged man, or a Brahmana deeply versed in the Vedas.

By killing an aggressor [âtatâyin] the slayer incurs no guilt, whether (he does it) publicly or secretly; in that case fury recoils upon fury.

The definition of atatayin has been put forth by Vasishtha Samhita (Chapter III: 11):

An incendiary, likewise a poisoner, one who holds a weapon in his hand (ready to kill), a robber, he who takes away land, and he who abducts (another man’s) wife, these six are called assassins (âtatâyin).

Sri Rama and Sri Krishna are traditionally hailed as great practitioners of Dharma but lived their life through exemplary opposition to the aggressors. They were unforgiving towards aggressors. Sri Buddha was against needless bloodshed but never appeared as a Pacifist. “Buddhist values are not simply pacifist, and Buddhist scripture and legend inform us that Avalokiteśvara [the deva of compassion] readily takes a warrior’s form when needed and supports the warfare of righteous kings.”[vii]

Ahimsa is not Passivity

Ahimsa is not Passivity

In spite of the general liberal attitude of Dharma-tradition, it does not stand for any neutrality towards the intolerant. This paradox arises from the fact that if the intolerant is tolerated, the intolerant devours the tolerant to remain the only voice. Therefore, tolerance for the intolerance is logically inconsistent. Rather the principle of ahimsa demands that a Dharma-practitioner must stop the intolerant to flourish at all costs. This is a principle which is easy to preach but perhaps most difficult to practise. It takes enormous amount of courage, determination and sacrifice to take up arms for the sole cause of practising ahimsa, without expecting any reward in this world. A true Dharma-based practice must endow the practitioner with such courage, determination, sacrifice and respect for Ahimsa.

[i] The definition has been provided by Swami Satyananda Saraswati who was a first-person-empiricist, in his Bengali work “Kramavikasher Pathe” (1934, The Path to Evolution).

[ii] The Grihya Sutras are texts containing information regarding Vedic domestic rites and rituals meant for the householders. The Grihya Sutras as their name suggests deal with domestic rituals such as conception, birth, initiation (upanayanam), marriage, death etc. Names of some of the Grihya Sutras are Sankhyayana-Grihya-sutra, Asvalayana-Grihya-sutra, Paraskara Grihya-sutra and Khadia Grihya sutra.

[iii] Kramavikasher Pathe, Chapter 7.

[iv] In the popular culture, Akira Kurosawa’s movie Rashomon is considered a masterpiece for elucidating the idea of relative reality

[v] Shanmukh, Saswati Sarkar, Divya Kumar Soti and Dikgaj, Was Gandhi a Christian in faith and Hindu in name?

[vi] Reflections on Gandhi, George Orwell. Available at http://www.orwell.ru/library/reviews/gandhi/english/e_gandhi

[vii] It’s not so strange for a Buddhist to endorse killing, Stephen Jenkins. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2011/may/11/buddhism-bin-laden-death-dalai-lama